GB3TD repeater

- Home

- Walking and Cycling

- Photography

- Amateur Radio - Introduction

- Slow Scan TV

- GB3TD Repeater

- Satellites

- Navtex - Marine Safety Info

- SDR - Software Defined Radio

- G2B - Special Contest Call

- Amateur Radio Contests

- QRP - Operating Notes

- Decoding FM DAB signals

- Decoding ADS-B

- Links to Useful Sites

- NOAA Weather Satellites

In the late 1980s and early to mid 1990s, stations on the 2m analogue FM repeaters were usually 'wall to wall' and the etiquette was to call "break please" in order to either enter the fray or call a station with whom you had perhaps arranged a 'sched'.

If I were to have jumped straight from 1990 to 2022; depending on the time I made the 'leap', I might quickly have made the obvious assumption that FM repeaters were no longer in use!

Some days, whilst out walking for several hours, I can access a mixture of 2m and 70cm repeaters - including GB3TD - and raise ... no-one.

GB3TD was recently switched to channel UR63, with an input frequency of 430.7875 MHz and an output of 438.3875 MHz. It has a CTCSS access tone of 118.8 Hz. This channel is shared with only 1 other repeater in the UK - in Wolverhampton - so GB3TD benefits from having no issues with potential signal overlap.

I have worked into GB3TD from in excess of 85 miles distance - on Exmoor - using 5W and a handheld HB9CV antenna and, quite recently, heard a station putting in a good signal from Southampton.

The repeater sensitivity appears to have improved further with the frequency change so it is hoped that even more 'DX' will be heard and for those - like me - who like to walk extensively, it 'holds' my 1 Watt signal nearly 100% of the time on walks of several miles and at distances around 17 miles!

I have managed to find an excellent piece of programming, courtesy of Basu Bhattacharya/VU2NSB, which he title’s his Propagation Path Profiler.

Tying this in with my exploits from Exmoor, Somerset has enabled me to get a much better idea of what happens - UHF radio wise - between there and the GB3TD repeater at Whitefield Hill.

It helps to explain how I am sometimes able to successfully access GB3TD from Exmoor, in Somerset 😀 and sometimes not. 😱

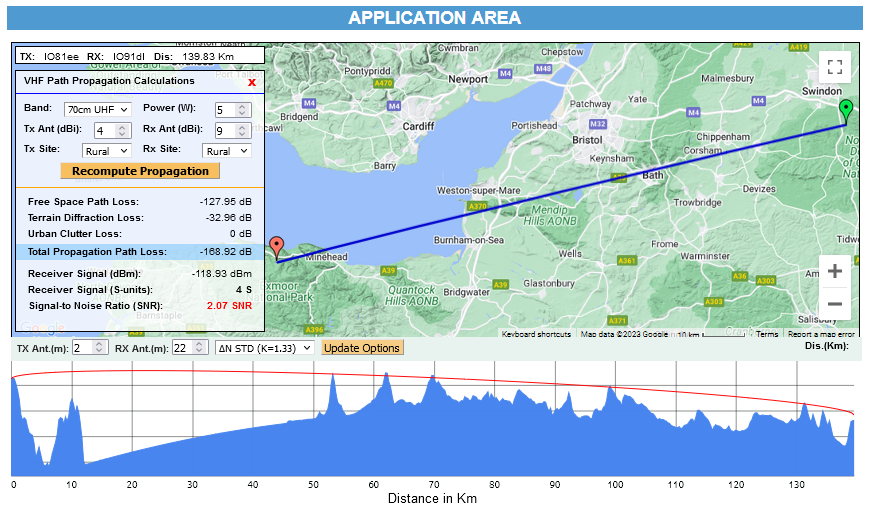

Using the application, I initially made two calculations; the first shows the theoretical losses and expected signal path under ‘normal’ atmospheric conditions; the second, under slightly enhanced conditions.

UHF signals are most affected by the tropospheric conditions prevailing at the time of transmission. As atmospheric pressure, temperature and relative humidity change, they produce a refractivity gradient in the troposphere.

In the way that light is bent away from its original direction when it encounters a prism, the radio waves experience a similar effect when they move to and from areas of varying density.

With normal refraction conditions, as – roughly – the atmosphere becomes more rarefied the higher you go, the signal will gradually bend back towards the Earth’s surface as the refractive index is, in general, higher towards the Earth’s surface. The radio signal horizon is marginally beyond the visual one by a factor of around 15%.

With super-refraction, the ‘refractivity gradient’ is much higher and so the signals are bent further down toward the Earth’s surface. This greatly extends the distance the signals can travel.

At higher levels still, ‘trapping’ occurs. This is when the signal is bent sufficiently for it to come back to the surface and be reflected back up again. If the trapping conditions extend further, then multiple ‘hops’ can occur. This region is often referred to as a ‘duct’.

If the signal falls short, it is known as sub-refraction; when the signal is bent upwards due to the refractive gradient being positive; i.e. density increasing with height.

So, how does all of the above play out with my findings when endeavouring to access GB3TD from Exmoor?

With ‘nominal’ figures, the results indicate a very poor SNR of 2.07 and may explain why, in general, a QSO is just about achievable.

The true terrain topographical profile shows several high spots that will directly interfere with the signal path.

Going from left to right, and looking at the points where blue peaks pierce the red line, we have the following:

- There are three close-by peaks here in the west Mendips; Crooks Peak at 186 metres, Wavering Down at 211 metres and Shute Shelve Hill at 232 metres.

- Here we have Beacon Batch, still in the Mendips, at 325 metres.

- The next one, still Mendips, looks to refer to Dundry Down at 223 metres.

- Moving on; it looks like we have Kingsdown Golf Club near Bath. Highest elevation is 176 metres.

- Finally is Hackpen Hill at 273 metres.

Of course, it is possible that under diffraction conditions, the signal could be bent around these obstacles. Another consideration to add to the fun of the hobby! 😀

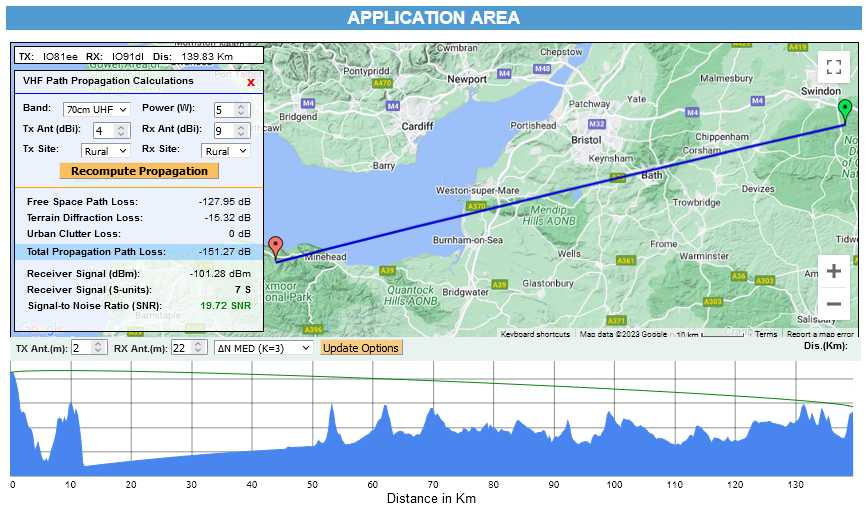

This second screenshot gives an idea of what might happen if the refractivity gradient were to increase marginally. This is the smallest change the profiler will allow and these conditions would be likely expected fairly frequently; e.g. during an early morning inversion when the signals would be refracted down towards the earth by the temperature-inversion boundary layer.

Now the effects of the high points along the path are greatly reduced, as the terrain diffraction loss drops away considerably, and the SNR rises to 19.72!

What I have discovered in reality is that it is critical to find the optimum point on the ground to provide the best opportunity for a QSO.

As I have carried this out a number of times now over the past 3 years or so, I know to the metre or two where to stand; I can even pick out the relevant gorse bushes! 😆

As signals between Exmoor and the GB3TD repeater are crossing land, the best time to operate will usually be at sunrise; the worst at mid-afternoon. The opposite would be the case for signals over water.

Large variations in signal strength and interference can be expected depending on local effects when using tropospheric propagation, often between locations only a few miles apart. This is especially true during elevated-ducting events, where elevation becomes increasingly important.

I have not included a diagram, to save space, but updating the antenna gain figure with the claimed gain of my HB9CV raises the SNR to around 8 under ‘flat’ conditions!

Thanks to all those who have been at the ‘other end’ when I have been attempting to access the repeater, especially Rob/G4XUT 😃 who has always shown a keen interest and provided me with very detailed signal reports!